This article is a two-part series which follows on from previous issues about the shopfitting industry in Queensland from 1860-1900. We now continue the journey as we take a look at some of the industry ‘players’ from 1900 onwards in Brisbane and provincial towns.

The first decade of the 20th century finds the beginning of some shopfitting companies that are still trading today and of others that are long gone. Brisbane and surrounds had a population of 122,210 and was made up of 20 municipalities and shires. The start of this century threw a lot at our industry, as Brisbane suffered an outbreak of the Bubonic Plague in 1901, a call to arms for the Boer War in 1902 and the outbreak of World War I in 1914. This was followed by the Spanish Flu in 1919, which saw 40% of the population at that time infected and in quarantine. The Queensland border was closed and food supplies and building materials were in short supply.

Still, at that time most of the shopfitting factories were based around the central city (‘The City’), Fortitude Valley (‘The Valley’) and Newstead areas, as the first small privately owned electricity generating supply companies were also in and around The City area. It was not until the 1920s, after the Brisbane City Council was established, that electricity was supplied to the suburbs.

As we move in to the 1900s in Brisbane and other provincial towns, we find that there was a flurry of building works that commenced state-wide just prior to the turn of the century. Large department stores were built, many of which are still standing today. There were cafés, clothing stores and arcades developed with a new sophistication being offered to the public, some even had electric lights and “cool air”.

The arcades were a version of the shopping centres that were yet to come. Some of the early ones were:

Royal Exhibition Arcade Brisbane

Grand Arcade Brisbane

Royal Arcade Charters Towers

Town Hall Arcade Townsville

Town Hall Arcade Brisbane

Rowes Arcade Brisbane

Grand Central Arcade Brisbane

Royal Red Arcade Ipswich

Mayfair Arcade Brisbane

Tattersalls Arcade Brisbane

Blocksidge & Ferguson Arcade Brisbane

Wallace Bishops Arcade Brisbane

MLC Arcade Brisbane

Brisbane Arcade

Piccadilly Arcade Brisbane

Comino’s Arcade Redcliffe.

In Brisbane, one of the department stores was Finney Isles, who built a store at 196 Queen St in 1909, which later became David Jones premises. Alan & Stark built various individual buildings from 1881-1899 and one at 110 Queen St, which in 1970 became Myer, prior to the building of the Myer Centre in 1988. Hardy Brothers Building at 116 Queen St was built in 1881 and occupied by Hardy Brothers Jewellers from 1894 until they relocated in 2016. They were only recently bought out by Wallace Bishops Jewellers.

Palings Company building, at 86 Queen St Brisbane was built as 4 individual, identical buildings from 1885 -1919. They were well known throughout Queensland for the supply of musical instruments, sheet music and later vinyl pop records from the swinging 60s until 1986.

At the start of the 20th century, the Brisbane Town Centre was expanding, and stores were opening at South Brisbane and Fortitude Valley. At South Brisbane in 1886 the early department store of Piggot and Bierne was built in Stanley St but burned down in 1891. The Valley was developing quickly as another shopping hub, with access now by train and trams from the northern and southern suburbs.

The Irish connection was heavily involved in the development of department stores in their early stages. With Piggots establishing a store in Brunswick St The Valley and in Toowoomba. T C Bierne opened opposite Piggots (his former business partner) in Brunswick St The Valley. (Piggot had been T C Biernes’ employer in Ireland).

James McWhirter (a Scotsman) had also opened a small store in Brunswick St, but he had grandiose plans. To start with, he bought out Piggots Brunswick St business then proceeded, as part of his plan, to purchase 4 blocks of land at the corner of Brunswick St/Wickham St and Warner Sts. Eventually, his 5-storey building took up an acre of land and was the leading store in The Valley. McWhirter, being an astute businessman, fitted out all levels of his department store in the latest fixtures and fittings, mainly in silky oak timber finishes and had the renowned beautiful large, glazed shopfront windows along Brunswick St.

McWhirters directly imported many lines and pioneered free carriage of mail orders servicing all parts of Queensland. In 1955, Myer Emporium took over the McWhirters company. In trying to not be outdone by McWhirters, in 1902 T C Bierne constructed a large building opposite, with further extensions over the years. In 1956 the building was sold to David Jones.

On the other corner of Brunswick St and Wickham St, Overells Drapery established in 1901, commenced the building of their department store to oppose McWhirters and T C Bierne. This also was a successful business and established stores throughout Queensland. In 1956, the large American Group Waltons purchased the building and the business. In these heady years, the local shopfitting companies in Brisbane City, Fortitude Valley and Newstead were all kept busy manufacturing and fitting out these department stores and the associated specialty stores. In 1905, shopfitters were earning 9 shillings a week for a 6-day, 48-hour week.

At this time, the other large department store to be built in The City was McDonnel & East, at 414 George St. The company commenced in 1901 in leased premises, also in George St but soon purchased adjacent land and finally in stages, built what is now on the Queensland Heritage Register, along with the other 3 buildings mentioned above. By 1988, with strong competition from suburban shopping centres such as Westfield and with the declining reputation and quality of the suburb, The Valley had become much less desirable as a shopping district and all 3 department stores had closed.

McDonnel and East traded successfully until 1990 and at that time had stores at Garden City Shopping Centre at Mt Gravatt (a suburb of Brisbane), Rockhampton Shopping Fair, Nerang St Mall Southport, Surfers Paradise Holiday City Centre, Toowoomba, Warwick and Ipswich. They also closed the well-known Pikes Menswear store at the top of Queen St, which they had acquired. Pikes had commenced trading prior to 1900.

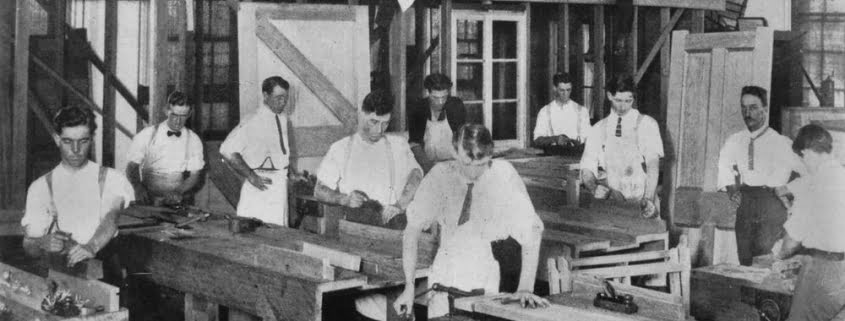

Prior to 1907 our industry Apprentices in Brisbane attended The Brisbane Technical College at 2 George St, The City. Then in 1907, plans were announced for a much larger modern Technical College, which was constructed in stages from then until 1956. This became QIT and later changed to QUT in 1987, as a University. The area is now known as Gardens Point Campus. In the 1960s the trades were moved out to campuses in the Northern and Southern suburbs of Brisbane, as well as to some Provincial Towns.

There were 34 cabinetmakers and upholsterers (as they referred to themselves) and 17 carpenter and joiner companies. Advertisements from the time, and because they had premises in The City, advertised as providing shopfitting, shop and office fitting and cabinetmaking services. It is interesting to sight these advertisements and the addresses of their factories, e.g. F W Thompson Shop and Office Fittings, Gilbert Place Queen St, opposite the Treasury Building, B Cunningham Builder and Shop & Office Fitter, 191 Elizabeth St and F H Marshall & Co. Builders and Shopfitters, 153-154 Elizabeth St, to mention a few.

Their only means of advertising their services were in the morning and afternoon newspapers, they also had to advertise for staff in the same newspapers. In the regional towns at this time there were generally 1 or 2 cabinetmakers or shopfitters, depending on the size of the town and evidence shows that if there were 2 cabinetmaker/shopfitters, then both advertised as the town undertakers. At that stage, Charters Towers, being a thriving Town, had 4 cabinetmaker/shopfitters, so it followed that 3 of the 4 companies were also listed as undertakers. In some advertisements of the time these companies advertised that they carried out the shop and office requirements of the town, as well as manufacturing coffins and carrying out burials, certainly an ‘upsell’ one could say.

One company name that keeps appearing in the research is R S Exton & Co. Robert Skerrett Exton was a prolific painter, decorator and glazier, who commenced business in Brisbane in 1882. The company also imported staff from the UK to assist with the production of stained glass works. They became famous for producing fine stained glass in the churches and cathedrals in Brisbane and throughout Queensland. They had purpose built their office/warehouse at 333 Ann St Brisbane City, the façade of which remains and is Heritage listed. They had a factory in Bowen St. The Valley and in 1919 they purchased another building in Wickham St. The Valley on the corner of Constance St and commenced their shopfitting and glazing department, which traded at that site until the 1970s.

They advertised that they manufactured all classes of modern shopfronts, showcases, banks, hotels and all general interior fittings, drawn sheath metal shopfront mouldings, nickel brackets, stripping for window fittings and all accessories pertaining to modern shopfittings and window displays. Their factory in Toowoomba also traded until the 1970s.

An R S Exton advertisement from the Brisbane Daily Mail in April 1922 reads, “Modernize Your Store, Success Depends Largely on Appearance. Shopfronts, Showcases and All Glass Counters Designed and Constructed for the Modern Businessman. Silent Salesmen that Work for You Day and Night.” Upon the closure of the business in the 1970s, several of the glaziers moved onto the likes of G James and the shopfitters to other shopfitting companies of the time.

Another company supporting the industry in The Central City area was the company S Cook & Sons, who had commenced in 1895 and remained in the area until 2001. They were electroplaters in nickel, chrome, tin, cadmium, zinc, silver, copper and brass. At one stage, they had 30 employees and the company, in the same family’s hands, still operates in a smaller way at the Northern Suburb of Arana Hills. A shopfitting company that was established in 1889 and still advertised until 1940, was E J Grigg & Son Pty Ltd. Their office and workshop was at Bowen St. The Valley, their advertising suggests they also completed many jobs in The City.

Another electroplating company in The City established in 1903 was A G Jackson Electroplaters. They carried out plating works for the industry but also had developed and patented shopfront window fittings. They also provided oxy and antique coppering and manufactured shopfitting’s to order.

In 1912, shopfitters were earning approx. 44 shillings for a 6-day 48-hour week. In the Brisbane 1912 Directory, there were 4 listed shopfitting companies, 38 cabinetmakers and upholsterers and 16 carpentry joinery companies and most offered shopfitting capabilities.

In 1912 the Brisbane business of T Early & Sons was established. Throughout the years they have been involved in producing freestanding commercial furniture, office fit-outs, and lift car interiors. The business still trades today and has been under the same family ownership all that time.

Also, in 1912 in Brisbane, a 7-week strike occurred and all factories, shops and hotels were closed down by 47 unions.

This has been reported as the world’s first strike. Around this time, a company by the name of D G Brims & Sons Joinery had started at Milton. They also had an adjacent sawmill and a business named Brisbane Aircraft & Automotive Engineering, where they made aeroplanes.

This business became prosperous during World War I, as they made products for aircraft and carried out repairs. They purchased land at Yeerongpilly in 1928 and installed a plywood mill as well as other manufacturing sections at that site. Later, in the 1960s they manufactured particle board products as they hit the scene and eventually rebadged as Brims Distributors, a business that lasted until the 2000s.

To be continued…